What Is Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS)?

The term “equine metabolic syndrome”, or EMS, was developed to describe the collection of risk factors associated with the disease. These include: obesity, insulin resistance (IR), and laminitis in horses and ponies. Horses with EMS can also concurrently have Pars Pituitary Intermedia Disease (PPID), also known as Equine Cushings Disease.

Stock horse mare with regional adiposity – fat deposits in the neck, withers, croup or base of the tail.

Hyperinsulinemia or Insulin Sensitivity

Hyperinsulinemia (high insulin in the blood) and insulin sensitivity are now highly recognised as an important factor in the development of laminitis in horses and ponies. Horses which already have high insulin are unable to regulate their blood glucose the same as a normal horse. Therefore, when a horse who is obese (highly likely to also have high insulin) continues to eat a high sugar diet (eg. green grass or high grain feeds) they will continue to have high levels of circulating insulin. Why does this cause laminitis? The research is still continuing. However, it is believed that the laminae are highly sensitive to the large amounts of circulating insulin, resulting in the development of laminitis.

Some breeds are naturally “good doers” and are at a higher risk of developing EMS

When should you be concerned?

Because laminitis affects a horse’s quality of life and can lead to death, horse owners need to be aware of the risk factors for EMS. Initially you should be concerned if you’d call your horse a “good doer” or “easy keeper”. These horses need a lower plane of nutrition. Although breeds such as the pony breeds, Arabians, Morgans and Quarter Horses mostly fall into this category, any horse or pony can be at risk. Laminitis can be mistaken for sole bruising, stiffness and arthritis, or foot soreness after trimming or shoeing. If episodes of foot soreness in the past have been associated with changes in available nutrition (eg early spring, after summer rain, and late autumn), then your warning alarms should be screaming loudly by now. Familial patterns are also a factor, therefore if your horse’s parents were “good doers”, then more than likely your horse is also.

Prevention

If your horse is predisposed to developing EMS, monitor its body condition carefully so the horse never becomes over conditioned, and be aware of the clinical signs – the cresty neck and fat deposits. Talk to us about your concerns. The ultimate goal is early detection to prevent laminitis from occurring.

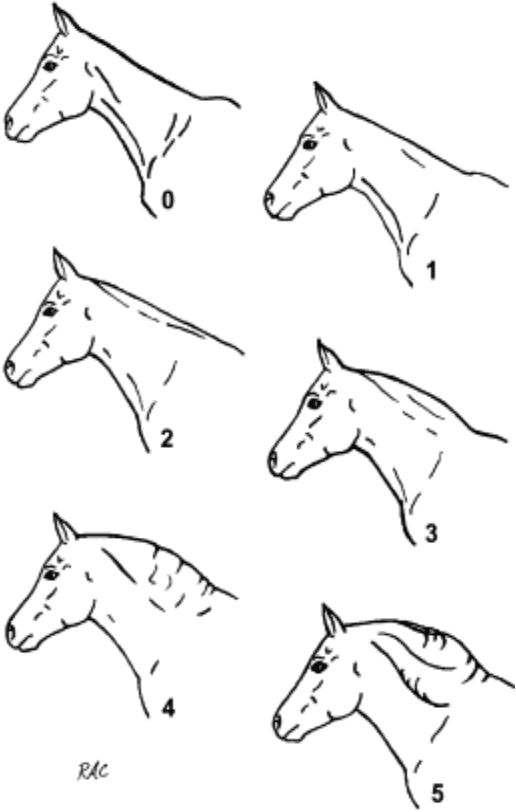

Does My Horse Have a Cresty Neck?

Source: Carter et al., 2009

There are six levels of crest. Ideally, your horse will fit a score of two or less.

0. No crest able to be felt.

1. No visual appearance of a crest, but slight filling can be felt.

2. Noticeable appearance of a crest, but fat deposited fairly evenly from poll to withers. Crest easily cupped in one hand and bent from side to side.

3. Crest is enlarged and thickened, so fat is deposited more heavily in middle of the neck than towards poll and withers, giving a mounded appearance. Crest fills cupped hand and begins losing side to side flexibility.

4. Crest grossly enlarged and thickened, and can no longer be cupped in one hand or easily bent from side to side. Crest may have wrinkles or creases perpendicular to the topline.

5. Crest is so large it permanently flops to one side.

When to call the Vet?

If the early clinical signs are recognised, we may be able to prevent laminitis from developing. Signs that we may look for in your horse include regional adiposity (fat deposits in the neck, withers, croup or base of the tail), general obesity, bilateral lameness attributable to laminitis (shortened stride, lameness on hard ground, positive response to hoof tester pressure, increased heat and digital pulses in the lower limbs, or reluctance to pick up feet), and/or signs of previous laminitis such as divergent growth rings on the hoof walls.

If you recognise any of these signs in your horse, call us on 02 6241 8888.

Fat deposits at shoulders, rump, hips and neck.

How do we diagnose EMS?

To commence our diagnosis of EMS, we use a combination of history, clinical signs and a thorough physical examination. We then follow this with screening tests for insulin resistance, which focus on the measurement of glucose and insulin concentrations. To properly assess insulin sensitivity, sometimes we need to do dynamic testing (fasting followed by administration of glucose or insulin). If your horse has a history of laminitis or is currently showing signs of foot pain, we will also take x-rays of the feet, to help guide our treatment plan.

How is EMS treated?

Unfortunately, EMS can never be cured. To protect your horse from developing the complications associated with EMS, a long term management solution is required.

Our overall goal is to reduce your horse’s body condition to a healthy 3/5, and a neck score of 2/5. We do this by reducing their total dietary intake and increasing the level of physical activity. We only exercise horses who are not experiencing laminitis, as this can place dangerous levels of stress on the already damaged laminae (further information on laminitis is in our Laminitis factsheet). If your horse has developed laminitis, we may also work closely with your farrier to develop a trimming/shoeing plan.

Because we know everyone and every horse is different, we will work out a diet and management strategy tailored to your individual circumstances. To arrange a visit for your horse from one of our dedicated equine vets, call us on 02 6241 8888.

Loading...

Loading...