Parasite (Worm) Control Guidelines

Worms are present in all horse, pony, donkey and mule populations worldwide and are considered the major health problem of these species. There have been recent changes in our understanding of worms and how to manage them. This document aims to address these changes and inform the horse owner of current recommended management practices for their horse(s).

Signs of Parasitism in the Horse

Signs of worm infestation are quite variable. The most common signs include:

- Poor growth

- Weight loss (looking ‘ribby’)

- Poor coat

- Colic (mild to severe)

- Tail rubbing

- Diarrhoea (loose or soft manure)

- Lethargy and lack of energy

- Anaemia (low red cells, pale or white gums)

- Death

Types of Worms

Large Strongyles (including Strongylus vulgaris, Strongylus equinus and Strongylus edentatus):

- Larvae are picked up and swallowed when horses are grazing.

- Lifecycle involves migration of larvae through blood vessels of the intestine and liver, where they cause inflammation and obstruction of the vessels. This causes disruption of blood supply to the bowel.

- Colic, ill-thrift and diarrhoea can be seen but this parasite is far less common today than it was 20-40 years ago.

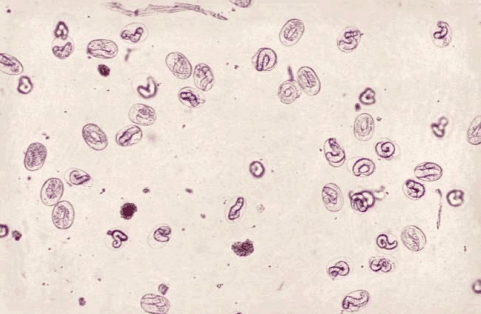

Small Strongyles (Cyathostomes):

- Currently, the primary worm of concern in the horse industry today.

- Eggs shed on the pasture remain infectious for at least 5 months and up to 9 months in the right cooler climatic conditions.

- When eaten by the horse while grazing, the worm larvae burrow into the gut wall where they encyst (hibernate) for many months or even years. They tend to emerge and migrate through the gut in the spring and summer, causing clinical signs. Migrating larvae through the gut can cause severe damage to the large colon, resulting in weight loss, colic and diarrhoea.

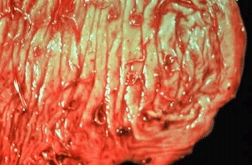

Severe inflammation and a thickened wall can result.

Tapeworms (Anoplocephala perfoliata):

- Tapeworms produce erosions of the gut mucosa at the attachment site, where they

latch on in clumps. - They cause impactions in the portion of the bowel that goes from the small intestine to the caecum (first part of the large intestine) and mild to severe, intermittent colic signs from slowed bowel motility.

- Weight loss rarely occurs.

- Treat for tapeworm in late winter once a year.

Roundworms (Parascaris equorum):

- Most important for causing ill-thrift and poor growth in foals. Migrating larvae may causing coughing and nasal discharge.

- Large infections can cause blockage (impaction) of the bowel and subsequent rupture (which is not treatable).

- Parasite eggs can remain in the soil for several years.

- Immunocompromised adult horses can also be susceptible to roundworm infections.

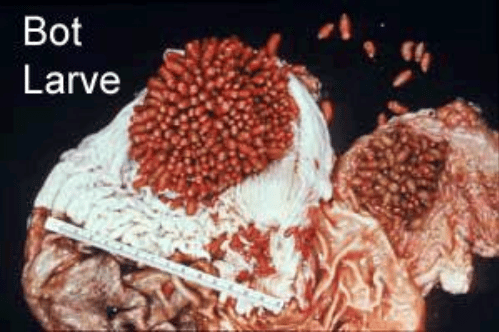

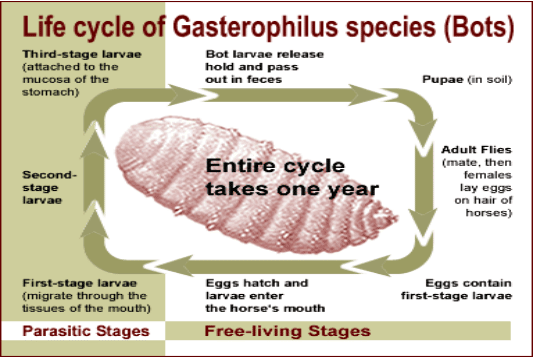

Bots (Gasterophilus species):

- Rarely cause clinical disease.

- Recommended to treat once a year in late autumn or early winter with an Ivermectin or Moxidectin product.

- Daily removal of the bot eggs from the haircoat will significantly reduce infection

Pinworms (Oxyuris equi):

- The secretions from female worms laying eggs around the anal and perineal region (under the tail) is very itchy.

- Relatively mild disease but causes intense tail rubbing and hairloss around the tail.

- Eggs can persist in the stable, on grooming tools, fence posts and in the environment for long periods. Hot water and disinfectants will help kill the eggs.

Threadworms (Strongyloides westeri):

- Usually infecting the intestines of young foals, this parasite can be transmitted from mares to foals via the milk.

- Typically, a strong immune response develops and the infection is kept under control as the foal matures, except when large doses of larvae are swallowed and foals are overcrowded or immunocompromised, severe diarrhoea can occur.

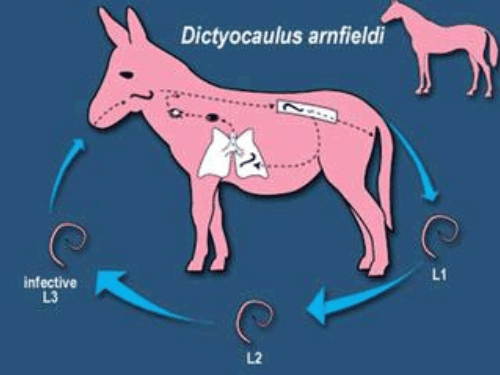

Lungworms (Dictyocaulus arnfieldi):

- The larvae of this worm can be found in the lungs of horses that live with donkeys and can cause parasitic bronchitis and bronchopneumonia.

“Get with the Times!”

Decades of frequent deworming has led to considerable resistance developing in particularly the small strongyle (cyathostome) and roundworm populations worldwide, and the Canberra region is no exception to this problem. The traditional approach of consistently deworming at regular 2-monthly intervals and rotating dewormers has created the resistance issue and the scary part of this is that there are no new deworming drugs expected to come onto the market for at least the next decade. That means we have to work with what dewormers we have available and use them sensibly to reduce resistance in our equine populations.

Important Definitions in Parasite Control

Anthelmintic: Another name for a drench, wormer or dewormer.

Parasite Resistance: The ability of worms to survive treatments that would generally be effective in killing that particular species and stage of infection (including eggs, larvae or adult worms). Resistance is an inherited trait passed between generations of parasites. This occurs when worms survive drenching and pass on their resistant genes to the next generation.

Refugia: It is important to have genetic variety in worm populations to avoid only resistant worms developing. This includes worms in an individual horse, paddock, farm and region. This population of surviving worms after drenching is called the refugia and genetic variety in the refugia will continue to make worms susceptible to drenching.

Reviewing Deworming Practices

The concept of deworming every 2 months came about around 40 years ago, when large strongyles were the main worm in horse populations and caused frequent death from ruptured blood vessels. As large strongyles have a 2 month life cycle, treating for them at regular intervals has reduced this problem in the horse and now we very rarely see large strongyles.

However, over these four decades, small strongyles have evolved to be the main parasite in horses and all grazing horses are infected. Thankfully small strongyles only cause disease when a horse has an extreme infestation and it is normal and actually useful for a horse to live with a low worm burden of small strongyles, (a refugia!). As the small strongyles, and other parasites that are the primary concern today have different life cycles to the large strongyles we treated in the past, it is not helpful and actually detrimental to drench every 2 months.

Therefore, frequent (2 monthly) deworming is no longer needed to keep adult horses healthy. What is required, are correctly timed treatments with effective dewormers to address the worm burden in the individual horse. Now is a great time of year to be reviewing our deworming practises.

Key Concepts to Keep in Mind for a Deworming Program

Please speak with a veterinarian to develop a plan that is tailored for your horse(s) and

management practices.

1. Adult horses (>3 years of age) and young horses (<3 years of age) need to be

managed differently due to different susceptibilities to parasites.

2. Adult horses are mainly infected with small strongyles, while young horses are more

commonly infected with roundworms. Tapeworms can cause colic in any age group.

3. Every individual horse has inbuilt differences in their susceptibility to parasites. Horses that are more susceptible to having worms will remain more susceptible their entire lives. These horses will always shed more eggs into the environment and are called ‘high shedders’. In fact, 20-30% of the horses on a farm will shed 80% of the eggs present on the pasture. Those horses with a higher innate resistance to parasites will remain more resistant their whole lives and therefore remain ‘low shedders’. This becomes an important feature of a deworming program, (see General Guidelines below).

Pasture Care:

- Regular removal of manure from the pasture.

For any worming program to be effective long-term, pasture management is critical. Regular (once-twice weekly or even daily) removal of manure from pasture is more helpful than drenching at controlling worms. Manure removal prevents larvae present in the manure spreading onto the pasture. Larvae migrate to 1 metre2 around each pile of manure so you can see how easily they can cover the entire pasture. - Avoid overstocking and overgrazing.

- Feed hay off the ground or in feed bins.

- Don’t spread non-composted manure on pasture.

This just allows the parasites to cover more ground and increases the level of parasite contamination. Parasite eggs and larvae can survive in freezing and hot, dry conditions. For instance, strongyle larvae need to be in temperatures over 40*C for 2 weeks to be eradicated. - Consider alternate grazing with cattle and sheep.

Parasites do not spread between these species and they will remove larvae infectious to horses from the pasture. - Don’t drench and put horses onto new pasture immediately.

Wait at least a week to move onto ‘clean’ pasture. Moving immediately prevents the critical step of developing a refugia and promotes survival of only resistant worms. - Pasture rested without any horses for 9 months should be ‘free’ of parasites.

The Modern Approach to Parasite Control

Small strongyle larvae can survive on pasture in appropriate, cooler climates for 6 to 9 months.

The new approach, recommended by Veterinary Associations worldwide, is to perform Faecal Egg Counts (Worm Tests) before every drenching! Clearly this is not always practical or financially feasible, so choosing the horses most at risk (older, younger or sick) or more valuable to test regularly may be a better option for most horse owners.

Regular monitoring (every 3 months) of the number of eggs in every horse on a pasture or at a barn, and only drenching those with a high worm burdens (greater than 200 eggs per gram of manure) is currently the best method for parasite management.

If the horse comes back with a low worm count, the drenching interval can be extended to every 6 months. Once a year, a blood sample should be collected to check for tapeworms and again, only horses with a high result should be treated.

All new horses coming onto a property should have manure sent for a faecal egg count and be

drenched accordingly before being allowed out with the new herd.

Even when a horse has consistently low faecal egg counts, once a year they should be dewormed with a moxidectin/praziquantel mix to treat for cyathostomes and tapeworms. The best time to do this is in Autumn (April-May).

Ensure not to under-dose horses when drenching- use scales or a weight tape to determine body weights and dose appropriately. Ensure the entire dose is consumed and don’t give the drench if the horse’s mouth is full of feed because it’s easier for them to spit it out!

But all this begs the question…

Which Drench Do I Use

If reasonable pasture management is maintained, drenching horses no more than every 3 months (4 times annually) should be adequate for worm control.

1. Ideally which drench to use is decided based on the results of a faecal egg count.

2. If you are not performing a faecal egg count, then use a drench containing only Ivermectin, Abermectin, Fenbendazole or Oxfenbendazole. Avoid combination drenches, that is drenches containing more than one product, unless you are specifically treating for tapeworms as well (see point 4 below).

3. The only dewormers effective against encysted small strongyles are a standard dose of Moxidectin (e.g. Equest) and a 5-day double-dose course of Fenbendazole (e.g. Panacur). These should only be used in the spring and autumn (once or twice annually) or after a high level of small strongyles that have not responded to previous treatments with drenches. If these drugs continue to be overused, we will have NO effective drugs to treat small strongyles on the market for at least the next decade.

4. The only dewormers effective against tapeworms are a double dose of Pyrantel (e.g. Strongid) and standard dose of Praziquantel (usually found in combination drenches). Treatment for tapeworm is usually only required in adult horses once per year in late autumn or winter due to the lifecycle of the parasite.

5. For treatment of bots, it is recommended to drench once a year in late autumn or early winter with an Ivermectin or Moxidectin product. Removing the bot eggs from the haircoat will significantly reduce infection.

6. NONE of the alternative, ‘natural’ remedies have been proven effective in controlling parasites in horses and are not recommended for parasite control.

Considerations for Foals, Weanlings and Yearlings

- Targeted treatment based on faecal egg counts is not recommended in this age group.

- During the first year of life, foals should receive a minimum of FOUR (4) drenches, starting at 2-3 months of age with Fenbendazole or Oxfenbendazole to treat for ascarids (roundworms).

- A second drench is recommended just before weaning at 6 months of age.

- A faecal egg count is recommended at this point to determine whether ascarids or strongyles need to be target and the next doses at 9 and 12 months should be based off these results.

- Tapeworm treatment should be included at the 9 month drench.

- Recently weaned foals should be turned out onto the ‘cleanest’ pasture with the lowest parasite burdens.

- Yearlings and two-year olds should be considered as ‘high-shedders and treated 3 to 4 times yearly